Kim Stanley Robinson probably is my favorite author, as recurrent readers of this blog might know. I have now read all of his novels – except for what is generally perceived as his magnum opus, the Mars trilogy, and 2018’s Red Moon – which I started but did not finish.

Kim Stanley Robinson probably is my favorite author, as recurrent readers of this blog might know. I have now read all of his novels – except for what is generally perceived as his magnum opus, the Mars trilogy, and 2018’s Red Moon – which I started but did not finish.

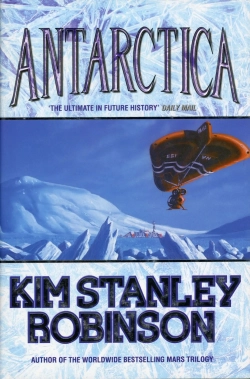

Antarctica is – like all of his other novels – unique in his oeuvre: Robinson never writes the same book twice.

At first sight it is a blend of near future adventure thriller, historical report, political treatise and landscape travelogue. But when I looked closer, rereading the parts I had highlighted to possibly quote here, it slowly dawned on me: this is KSR’s big epistemic novel. It is epistemology that subtly & cleverly holds together the different themes of this book: storytelling, imagination, science, ethics, politics, economics, the reality of nature.

As such, it might be the richest book Robinson has written – at least from an philosophical point of view. Robinson convincingly ties utopia and science together once and for all: this is no scifi, but realistic fiction about the essence & scope of science.

More on all that after the next few paragraphs, after the jump.

Robinson has a love relationship with the antarctic continent, and he has visited it twice – the first time in 1995, with the Artists & Writers program of the US National Science Foundation, and a second time, with NSF as well, in 2016.

And just like his other landscape infatuation – the Sierra Nevada – that love will result in a non-fiction book about Antarctica. In an interview for The Weekly Anthropocene earlier this year, Robinson said he would turn in the book to his publisher this July.

It’s structured like my book The High Sierra: A Love Story — the same format, in that it will have a variety of modes, including lyric realism as you called it, memoir, history, geology, and this case, glaciology. I’m enjoying this kind of modular miscellany, or just the kitchen sink principle— just throw in everything. It helps me to do non-fiction. (…) I love novels with all my heart. It’s what I’ve devoted my life to. But after Ministry, I don’t know what fiction to write next. So these nonfiction books fill a gap. They are a way of keeping my hand in the game while I try to collect myself for another novel.

It will be interesting to read that forthcoming book, and see how much overlap there is with Antarctica – as that novel has a significant amount of non-fiction too.