“Some people grumble about monotony, – such complaints are the marks of immaturity, sensible people don’t like things happening.”

I have no idea how this book first showed up on my radar, but, speculative fiction aside, I do have a bit of a sweet spot for tales of rural epic loners taking on life, their farm or their craft. Marlen Haushofer The Wall falls in this category, as well as Felix Timmerman’s A Peasant’s Psalm and even The Door by Magda Szabó fits.

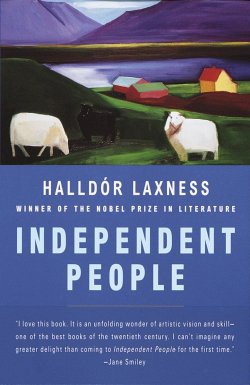

So when I learned this book basically won Halldór Laxness the Nobel Prize in 1955, and, more recently, has been more and more heralded as one of the greatest novels ever written, I decided to take its measure too.

Independent People was first published in Icelandic as Sjálfstætt fólk in two volumes, in 1934 and 1935.

Laxness’ works have been translated in 47 languages, this book in 35. The sole English translation dates from 1945 and was done by James Anderson Thompson. It was an immediate success when it was published in the US in 1946, selling nearly half a million copies. But as parts of this novel deal with socialistic reform in Iceland – more on that later – Laxness became the victim of McCarthyism, and his career in the US was destroyed by deliberate machinations of the American government.

It had been out of print for decades in the US, but at the end of the 20th century a glowing article by Brad Leithauser and a reissue slowly pushed it closer to the center of the canon of Western literature again, and now it’s often ranked in serious lists among the best books ever.

So, what’s it about – and did I like it?

Independent People is set in the first decades of the 20th century, and focuses on Guðbjartur Jónsson, an Icelandic crofter who struggles to gain independence. The novel starts as Bjartur, after 18 years of toiling for a wage, manages to put down the first payment for his own sheep farm, Summerhouses – in a valley once cursed by Kolumkilli, a dead sorcerer-saint. Bjartur and his family live a poor, isolated life: his dog is lousy, his sheep are wormed, and there is no real furniture in their hut. Conditions on the Icelandic marshes are harsh, and winters are long and lethal.

Laxness’ protagonist is one of the most compelling characters I have ever read about: Bjartur is gripping because he is both absolutely heroic, and yet a stubborn, misguided & utter fool – a bigot about his ideas of independence, even though he is a skeptic. That makes Independent People both a harsh & epic saga, as well as a tragic, deadpan comedy.

As if that alone wouldn’t have been enough, Laxness also wrote a book that has things to say about power, money and society. I will not dwell on this aspect too long, as Marc Magill already wrote an excellent piece on Automachination. Worth quoting is part of his conclusion, on why this isn’t really a socialist socialist novel:

This is why I refuse to classify this as a socialist novel. Instead Halldor Laxness portrays a world where our own neuroses and insecurity, and judgment of one another, keeps us separated. (…) The belief systems that make us succeed will often make us discount others who haven’t, and the limited nature of our perspectives makes those people into failures. Socialist novels are intended to inspire revolution, even Grapes of Wrath makes a good go at it. Instead, Independent People shows the evil and tyranny of the world system and explains it, subtly, and then suggests that you can do little about it. The best you can hope for is comfort, and the ability to escape into fantasy.

While Bjartur is a character I will never forget – dementia notwithstanding – I have to admit at times I struggled with this book. The prose is dense, and always needs your attention. It is generally rewarding – there are some great, great lines, images and scenes throughout the book – but it also drains your energy, and I admit that occasionally I was a bit too tired – work, kids – for my mind to really do the writing justice.

Aside from the prose, especially in the second half of the book certain details about the farmer’s cooperation and other stuff too didn’t always grip my attention. For my tastes Laxness could have cut about 40 or 60 pages from this tightly set 482 page tome. I don’t think the book would have suffered if the focus had been solely on Bjartur and his ilk throughout – even though I admit that his political and economic surroundings are crucial to the story.

Bjartur is of the strong, silent type, and he buries his stillborn children without tears. This is not to say there is no longing or love in these pages. The relationship between him and Asta Sollilja, Bjartur’s daughter who is not of his own blood, is touching, and a sharp portrayal of a time and a culture wherein people were ill-informed about their own psychology, reluctant to express themselves, and as a result much more lonely than they need have been.

Laxness’ naturalist novel is a triumph as it lures people in with a promising title, seemingly waving the banner of meritocracy, but slowly shows true independence does not exist, not at all, and it turns out nobody even knows what ‘freedom’ is. It all culminates in the fleeting moment Bjartur and his fellow Icelandic farmers make heaps of money because World War 1 has driven up the demand for their mutton and their wool: their success the result of other people’s misery.

Your mileage may vary, but Independent People is at the least worth looking into. So if any of the above sounds interesting to you, I would like to point you at Annie Dillard’s review in The New York Times, who does a much better job at selling the book than I could. Take her text with a grain of salt though, because this is a rich book and there is more than plenty for the eyes of the beholders. Anybody’s take on Independent People is just that: a take – not an independent take, but private nonetheless.

I do unequivocally recommended it for Ayn Rand fans!

NB – In het Nederlands verschenen er twee vertalingen: Vrije Mannen, vertaald via een Deense vertaling door Annie Posthumus, in 1938, en heel wat later Onafhankelijke Mensen, vertaald door Marcel Otten, rechtstreeks uit het Ijslands, in 2005.

Consult the author index for my other reviews, or my favorite lists.

Click here for an index of my non-fiction or art book reviews, and here for an index of my longer fiction reviews of a more scholarly & philosophical nature.

If this is promulgating the idea that there is no freedom, I can see why you ate this up with a spoon 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha, yes, I guess you are right. On the other hand, I don’t think the book has very much to say about actual freedom – the question really is what freedom is, and I’m not sure Laxness had an idea about that himself. It is about the idea that there is no independence though, and who can argue with that?

(This book also has something of Job by the way.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

If I still had a brain, that last parenthetical would have me reading: Pride’s Children is a modern retelling of the Book of Job. It’s interesting, since many moderns have no idea what that is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, the Bible clearly isn’t part of the canon anymore for a lot of young people.

LikeLike

At nearly 500 pages of unrelenting bleakness I may give this a pass (not least because I already have a couple of unrelenting Icelandic noir titles still to read) but I did appreciate your descriptive critique, thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It´s definitely not only bleakness, as there is lots of (black) comedy in this too, lots of beauty, and even sympathy & feelings.

But the general frame is one of a bleak, hard life indeed, so I 100% get your pass.

What are those Icelandic noir titles you want to read, if I may ask – I´m think I want to read more Icelandic stuff because of this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yrsa Sigurdardottir’s The Silence of the Sea and Ragnar Jónasson’s The Darkness are the titles I’ve got waiting for me, which I might get around to this winter, or next.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, will look into those!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for telling us about this novel! I am not likely to buy it, but it does sound like something interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You´re welcome. It has some mythic overtones at times, but otherwise its pretty far removed from speculative fiction.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting! I don’t think I will be rushing to read it, but I will keep this title in mind, bleakness notwithstanding. Glad you managed to enjoy it, Bart!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It might appeal to New Zeelanders, don´t you have lots op sheep as well?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me personally? Not even one 🤣

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ok, I added this to my list, it might take a while, but I’ll read it 🙂

There’s an interesting recent animated adaptation of Polish classic novel, The Peasants. I think I mentioned it when we were discussing Timmermans, take a look if you have a chance. It’s quite good – although they made some shortcuts, the book is almost sociological, this is a more condensed story about a Polish village before WWI.

LikeLike