This time, two books from an artist couple also featured in my favorite art book list I posted back in 2017. The first is a monograph from 2007 I’ve had for ages, but never got around to actually reading. The second book was published last year, and it’s the first posthumous monograph about the Bechers to appear, published to accompany the exhibition in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, an exhibition that traveled to San Fransisco, and is still on display until April 2, 2023.

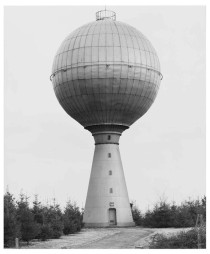

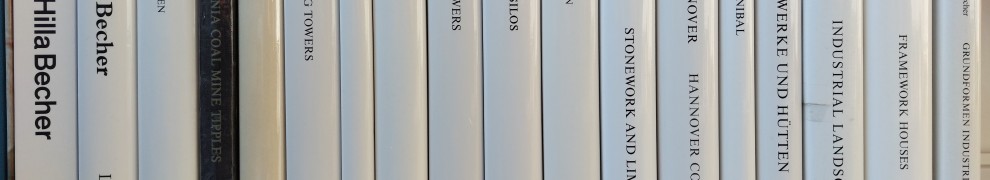

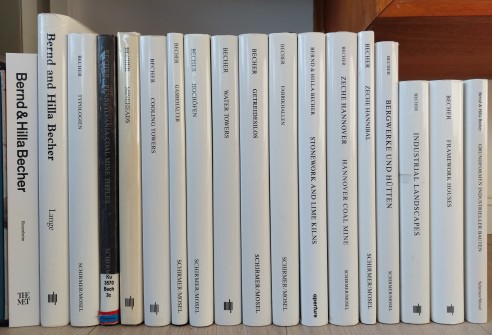

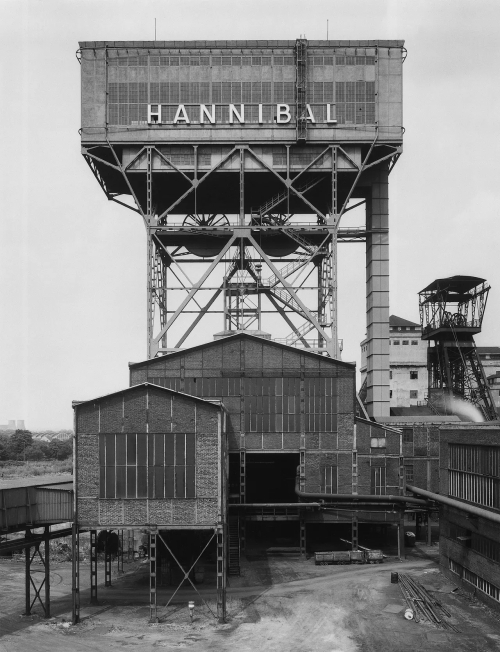

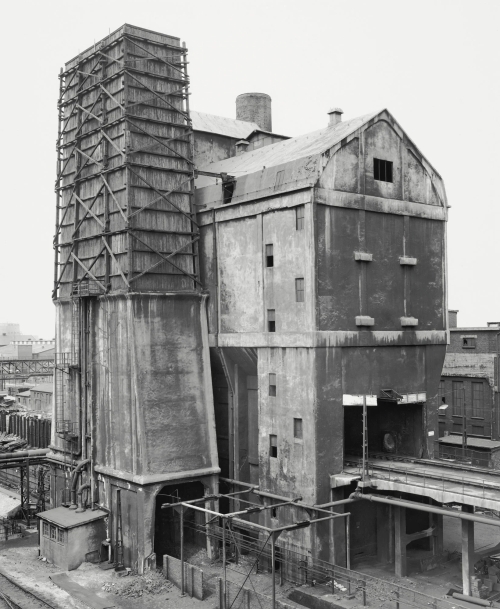

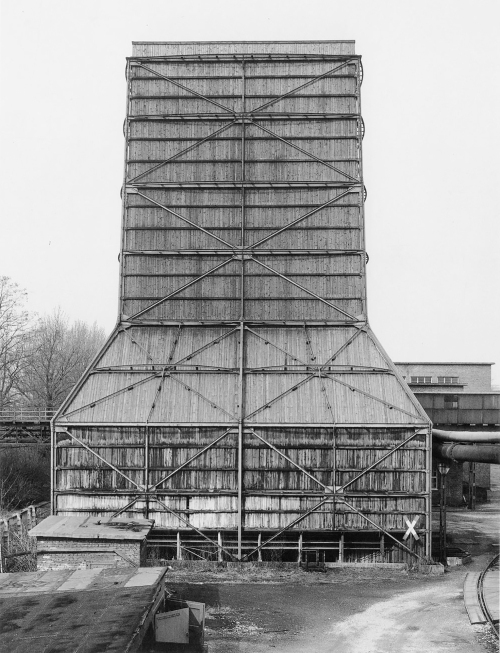

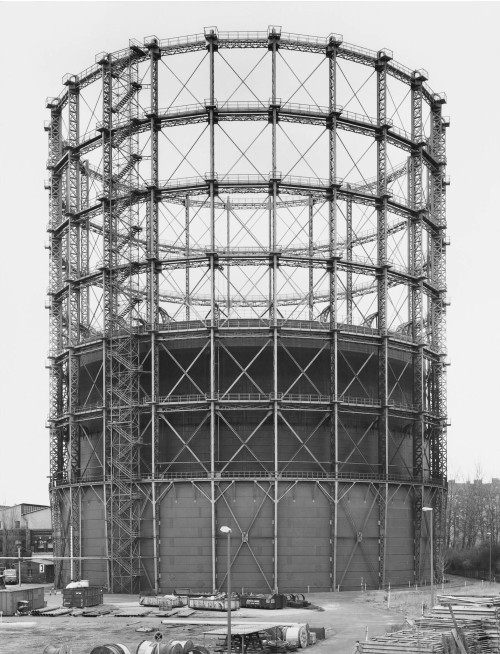

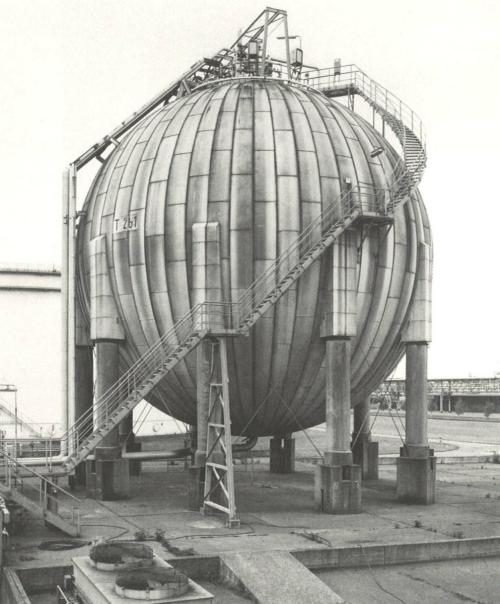

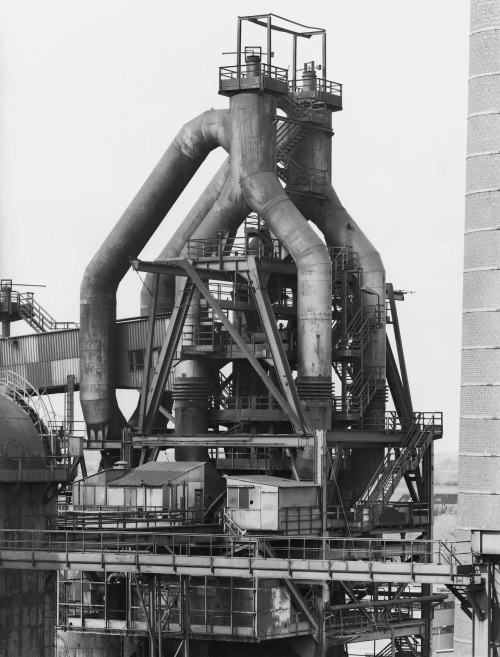

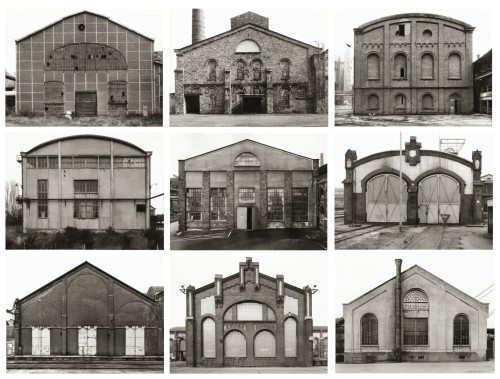

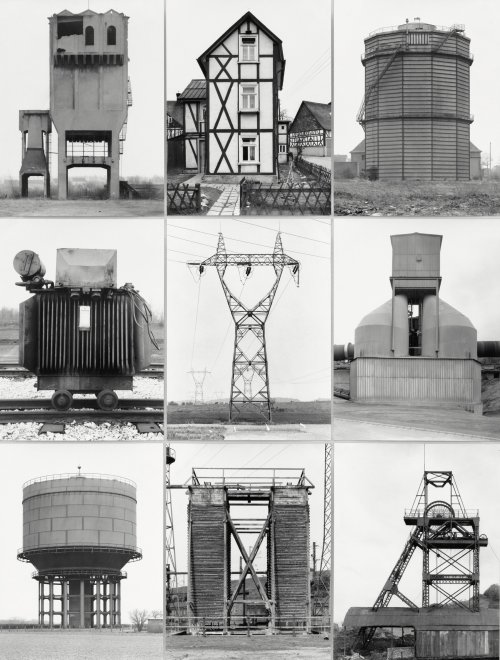

Over the years, I’ve steadily collected all the thematic monographs Bernd and Hilla Becher published – my collection is pictured above. Their work resonates deeply with me, and as their work is among the most revered of 20th century photographers, I know I’m not the only one. For almost 50 years the Bechers documented mine winding towers, blast furnaces, gas tanks, grain elevators, water and cooling towers, processing plants, factory halls, lime kilns, timber framed houses and entire complexes of factory buildings. They did so in much of Western Europe, and the United States as well. In a way, the things they depict are more machines than buildings, as critic Armin Zweite wrote.

Bernd also taught photography at the Düsseldorf Academy from 1976 to 1996, and Hilla was intricately involved with that too. This resulted in the so-called Becher school of photography, with prominent German artists like Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Axel Hütte, Thomas Ruff & Thomas Struth.

Both books at hand cover similar territory: they try to provide an overview of Bernd & Hilla Becher’s life and work, framed in an historical context. Is one markedly better than the other? And, more importantly, what did I learn from these books about the Bechers and their work? Why does it resonate so deeply with me?

BERND AND HILLA BECHER: LIFE AND WORK – Susanne Lange (2005, transl. 2007)

For starters, the oldest title. It was first published in 2005 as Bernd und Hilla Becker – Was wir tun, ist letzlich Geschichten erzählen … Einführung in Leben und Werk by Schirmer/Mosel, and issued in 2007 by MIT Press in a translation of Jeremy Gaines.

For starters, the oldest title. It was first published in 2005 as Bernd und Hilla Becker – Was wir tun, ist letzlich Geschichten erzählen … Einführung in Leben und Werk by Schirmer/Mosel, and issued in 2007 by MIT Press in a translation of Jeremy Gaines.

It has 248 pages, with 53 full page duotone plates and 126 additional illustrations. As for text: there is an essay of about 80 pages by Susanne Lange, 32 pages with three interviews, 8 pages of journal notes by Hilla Becher and 19 pages of bibliography, amongst other things. Print quality is top-notch.

Susanne Lange had a long working relationship with the Bechers, and also did her PhD about them. The depth of her understanding shows in the entire book – a book easy to recommend.

An important thing to understand about the Bechers is that they wanted originality. When Bernd saw the work of Paul Citroen in 1958, he immediately abandoned his own collage practice, as he realized “that the artistic path he had taken was, formally speaking, already well trodden and stylistically complete.” This aspect is easily overlooked nowadays, as their work might come across as stereotypical in its seeming generic objectivity.

What makes their work so interesting to me is the tension between this apparent objectivity as a result of a seemingly absent artist, and the fact that their images could have only been made by rigorous, dedicated and single minded artists. This seemingly absent authorship is only achieved by the fact that the Bechers were very much the authors of their photographs. If there is one thing this book shows is that the effort needed to get the right vantage point (set-up at times taking half a day, often involving ladders, dangerous climbing with heavy photographic material, on nearby buildings, roofs or structures, exposure to gasses and heat, etc.), the right light conditions (at times resulting in days of waiting in motels or their VW van), and even the right selection of which buildings to photograph (involving lots of research and social and legal maneuvering – sometimes for months – to get the needed permissions) was very, very substantial.

That selection of the photographed material is also often overlooked, as if the Bechers only wanted to document as many of these buildings as possible, before they were destroyed. This idea was partly instigated by Bernd himself, as what drew him to photography in the first place was its speed, as he couldn’t draw the buildings in his native Siegen, North Rhine-Westphalia, fast enough before they were torn down. So their work indeed has aspects of conservation, yet the aesthetic concerns are more important: they only took pictures of things they felt suited their aesthetic and formal criteria, things that gave as much visual information about certain types of structures as possible. Quality is much more important than quantity in their work – again something seemingly paradoxical if you just take into account the number of photographs they’ve taken, forgetting it took two full and long lives to take them.

What also draws me to their work is that the Becher’s themselves were not concerned with the question whether or not their pictures were ‘art’. Their work ticks a lot of boxes: it is photography, at the same time aesthetic and social & historical documentation, and it relates to architecture and sculpture – their first publication was called Anonyme Skulpturen, and they even won the Golden Lion for Sculpture at the 1990 Venice Biennial. It is also related to conceptual art and minimal art, yet it is its own thing and the Bechers developed their work independent of these schools. The same goes for New Objectivity of the 1920s, which did inspire them. At the beginning of their career, they operated outside the art world, publishing their work in corporate publications and architecture journals.

Maybe most importantly for their appeal, there are very important aspects of love and dedication to their work. For starters, there’s the aspect of them being lovers, making work as a team, rendering it unimportant who precisely made this photograph or developed that print, and resulting in art & life that were entwined. But there is also the love for plain reality, the Bechers in a way being eccentric collectors, finding beauty in a place where others didn’t find beauty before. I don’t think it is an understatement at all that the Bechers indeed taught their public to see the world with new eyes, as I will explain later. In the words of Hilla Becher herself, it boils down to this:

We undertook the work for the sheer visual pleasure we knew it would bring us, pleasure from remarkable shapes, which might be generally considered to be beautiful or ugly, but which existed primarily and originally for nonaesthetic, nonvisual reasons. We wanted to discover such shapes and, with the help of photography, to collect them. [1968]

It results in work that does not need interpretation. It is work that does not moralize. It just is what it is, and I have always been drawn to such art – be it Rembrandt, Roman Signer, Van Gogh or James Turrell.

I’m also inspired by them being so singular: they did one thing, and they stuck to it, from 1959 to Bernd’s death in 2007, and after that Hilla (née Wobeser) continued to reassemble their work, mostly using existing photographs. It is striking that during these 5 decades there is no “artistic development” in their work – in the usual sense of the word.

Our work has remained the same over the years. However, we do not have the feeling we have become stuck. Quite the contrary, as with every object we photograph, our eye becomes sharper in respect to the attributes perceived so that today we see much more clearly and can decide much more quickly and with more certainty which object possesses the elements of an object family or object type in a more or less typically ideal form. Consequently we can avoid photographing a whole range of other objects that are less typically ideal. Given the volume of objects we photograph it is important to choose those that innately combine as much visual information as possible. [from an interview with both Bernd & Hilla,1989]

A final aspect of their oeuvre’s appeal obviously is what is pictured. In a way, it is a testament to human creativity and problem solving: builders building buildings that fulfill a specific function. The buildings the Bechers photograph were build for profit, not for ideas or values, unlike many other architecture that survives – churches & palaces. The things they photograph don’t have a need to leave a good impression, and in that sense they are honest buildings, demolished if they aren’t used anymore. Most weren’t even designed by a single architect, but a collaborative effort. Their documentation shows both order and craziness, both similarities and difference & variety. The Bechers provide a look at a certain aspect of human existence, and, objectivity not withstanding, there is a certain melancholy tied to all that – especially as the industrialization is changing our biosphere.

BERND & HILLA BECHER – Jeff L. Rosenheim (2022)

Similar in length and scope, but much more recent is the publication accompanying the 2022-2023 exhibitions in The Met and the SFMOMA. It has 282 pages, filled with 217 illustrations, of which 103 take up a full page or two pages. Print quality is excellent. There’s a 30-page biographical essay by Virginia Heckert, 26 pages by Gabriele Conrath-Scholl presenting a case study of the Concardia Mine, 10 pages by Lucy Sante on the history of art depicting industry, and a 40-page interview with Max Becher, the couple’s son, conducted in 2021 by Jeff Rosenheim. There’s also a 4-page bibliography and a 6-page index.

Similar in length and scope, but much more recent is the publication accompanying the 2022-2023 exhibitions in The Met and the SFMOMA. It has 282 pages, filled with 217 illustrations, of which 103 take up a full page or two pages. Print quality is excellent. There’s a 30-page biographical essay by Virginia Heckert, 26 pages by Gabriele Conrath-Scholl presenting a case study of the Concardia Mine, 10 pages by Lucy Sante on the history of art depicting industry, and a 40-page interview with Max Becher, the couple’s son, conducted in 2021 by Jeff Rosenheim. There’s also a 4-page bibliography and a 6-page index.

There isn’t a whole lot of new to be learned if you have read the book by Susanne Lange. There are more illustrations in this book, but it does not feel significantly so – the only category of illustrations that’s here that’s not in the Lange is one page with 10 exhibition posters.

The fact that the main texts were written by 3 different people also makes for significant overlap among the three essays too, which is a bit annoying if you read this cover to cover. It’s frankly baffling the editors didn’t fix this. That said, this recent monograph is a solid publication, and I would recommend it, especially if you haven’t read the Lange. I had read that, and I still enjoyed reading this. Especially the long interview with Max Becher is valuable.

The most significant omission in the entire book is the story about Bernd giving up collages: I feel that illustrates their need for originality clearly, and that’s important in the light of their seemingly impersonal work.

Hecker quotes Thierry de Duve: “the admirable reserve of the Bechers’ photos, their unique way of being devoid of style, their formal uniformity…. You’d have to be blind to the profound motivation of their work not see that they eliminate all personal style from their photo – or sculptures – only to better release the impersonal aesthetics.” It is again the same paradox: by eliminating the personal, they created a very distinct style nonetheless.

Hecker also writes that Hilla Becher “would come to believe that photographs were most successful when they enabled viewers to make their own associations and interpretations.” I feel this is related to what Roland Barthes expressed in his 1967 essay The Death of the Author, and as such I think there is an easily overlooked kinship between the Bechers and post-structuralism, even if their work – especially the typologies – seems structuralist in approach.

An interesting quote that’s missing in the Lange book is one by Bernd in 1974: “Our work has the character of a collection. We collect objects – not actually interested in photography.” And in 1971 they said: “We deal with objects, not motifs. The photograph serves as a stand-in for the object – it is useless as a picture in the conventional sense. The information we see to communicate arises only in the series, in the juxtaposition of objects, whether similar or dissimilar, that perform the same function.”

To end this review, I’ll highlight two things I found illuminating from the interview with Max Becher.

The first is a passage in which he explains his parents weren’t big on Joseph Beuys, who also taught in Düsseldorf at the same time as Bernd. They didn’t like the idea of the artist as a mystic.

And finally, the notion that there is a Duchampian idea to their work, that is also about “educating the eye”. It is undoubtedly so that the Bechers strongly influenced the way we look at architecture – and more broadly reality – today. In a way, this is tied to the love and pleasure I talked about above:

“So, it’s the cultural training. Expanding the eye of the public is the mission. It is to help you see. The more you photograph the more you see, and the more aware you are. And the world becomes a nicer, richer place.“

I think this is one of the important functions of art: not so much change reality, but change our perceptions of it. It is not unlike the pun that used to be on tote bags of Tate Modern: “changing perspectives”.

Consult the author index for my other reviews, or my favorite lists.

Click here for an index of my non-fiction & art book reviews only, and here for an index of my longer fiction reviews of a more scholarly & philosophical nature.

You know how you are always worrying about free will? Don’t. In a couple of decades the machines will have it and then kill us all, so our worries will be over 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh but I’m not worrying about free will at all. It’s just something I like to write about here, and I like discussing it with people who have a different opinion about it, but apart from that, I’m totally unconcerned. Things are as they are, there is no free will, and I’m fully at peace with that.

As for killing machines: as a teenager I have long thought Terminator 2 was the best movie of all time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ahhh, so it’s just your mental masterbatory aid then. I’ll remember that.

Yep, T2 was even better than the original….

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is pretty interesting. Really intriguing structures on display. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you like it. I’d say it’s well worth exploring their work a bit more, if you like what you see.

LikeLike

Pingback: FAVORITE ART BOOKS | Weighing a pig doesn't fatten it.