Kim Stanley Robinson probably is my favorite author, as recurrent readers of this blog might know. I have now read all of his novels – except for what is generally perceived as his magnum opus, the Mars trilogy, and 2018’s Red Moon – which I started but did not finish.

Kim Stanley Robinson probably is my favorite author, as recurrent readers of this blog might know. I have now read all of his novels – except for what is generally perceived as his magnum opus, the Mars trilogy, and 2018’s Red Moon – which I started but did not finish.

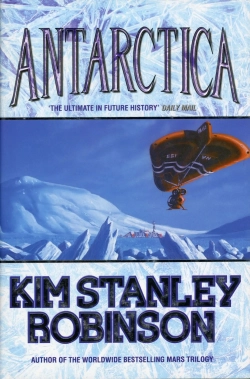

Antarctica is – like all of his other novels – unique in his oeuvre: Robinson never writes the same book twice.

At first sight it is a blend of near future adventure thriller, historical report, political treatise and landscape travelogue. But when I looked closer, rereading the parts I had highlighted to possibly quote here, it slowly dawned on me: this is KSR’s big epistemic novel. It is epistemology that subtly & cleverly holds together the different themes of this book: storytelling, imagination, science, ethics, politics, economics, the reality of nature.

As such, it might be the richest book Robinson has written – at least from an philosophical point of view. Robinson convincingly ties utopia and science together once and for all: this is no scifi, but realistic fiction about the essence & scope of science.

More on all that after the next few paragraphs, after the jump.

Robinson has a love relationship with the antarctic continent, and he has visited it twice – the first time in 1995, with the Artists & Writers program of the US National Science Foundation, and a second time, with NSF as well, in 2016.

And just like his other landscape infatuation – the Sierra Nevada – that love will result in a non-fiction book about Antarctica. In an interview for The Weekly Anthropocene earlier this year, Robinson said he would turn in the book to his publisher this July.

It’s structured like my book The High Sierra: A Love Story — the same format, in that it will have a variety of modes, including lyric realism as you called it, memoir, history, geology, and this case, glaciology. I’m enjoying this kind of modular miscellany, or just the kitchen sink principle— just throw in everything. It helps me to do non-fiction. (…) I love novels with all my heart. It’s what I’ve devoted my life to. But after Ministry, I don’t know what fiction to write next. So these nonfiction books fill a gap. They are a way of keeping my hand in the game while I try to collect myself for another novel.

It will be interesting to read that forthcoming book, and see how much overlap there is with Antarctica – as that novel has a significant amount of non-fiction too.

I think the most central question to the novel is the question about what facts are – and that’s at heart an epistemological question. This is most clear in Robinson’s inclusion of the Sirius debate, a controversy about the age of glacial sediments and their significance for understanding past ice-sheet stability. Robinson uses it to illustrate how science, as a procedure, works.

But of course it was not actually a cliff of facts, but of sandstone. Interpretations were open to argument, at least until the matter was firmly pinned down and black-boxed, as Geoffrey put it, meaning become something that all the scientists working in that field took for granted, going on to further questions. (…) As they had not black-boxed this particular question, it was still sandstone only and not yet fact.

But Robinson is not necessarily interested in facts as facts, or even in science for the sake of science, but crucially also ties it to how ‘facts’ are perceived & used in politics. Different people can react very differently to the same set of inputs: both Democrats and Republicans live in the same country. Robinson voices something that has puzzled some people on the left for a long time: how come people that are poorly paid tend to vote contrary to their own interests?

‘Yes but why, Wade, why? How do these people win elections? I have never understood why so many decent hardworking Americans will loyally, and you have to say pigheadedly, continue to vote for people whose explicit declared project is to rip them off. (…) Cutting jobs, reducing wages, increasing hours, shaving benefits and retirements – all this downsizing is the downsizing of labour costs, meaning less of what companies make is given to the employees and more to the owners and shareholders. And this is the Republican programme! They advocate this transfer of profits! (…) how do they do it?’ ‘They tell people it’s Democrats ripping them off, with taxes. People see business paying them and government taking it away.’ ‘But business takes it away too! They take it first and they take more and then they run off with it! People are just squeaking buy while their employers are zillionaires! At least if the government rips you off then they use the money to build roads and schools and airports and jails and all, they build the whole damn infrastructure! (…) The owners just take the money and build castles in Barbados. How can they justify that, how can they sell that programme?’ ‘Ideology is powerful.’ ‘I guess so. You must be right. Although I’ve never understood why you can’t look the situation in the face and see what’s going on.’ ‘An imaginary relationship to a real situation.’

The answer is clear: it’s all about the interpretation of facts. Facts are, just as in science, not really facts to begin with. Ideology is crucial, and Robinson echoes my favorite definition of ideology, that of Louis Althusser: “Ideology represents the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence.”

The word ‘imagination’ in that definition is of interest to Robinson as well, and imagination is another strong theme throughout Antarctica.

For starters, imagination is clearly tied to utopia, as literary critic and KSR mentor Fredric Jameson pointed out about the Mars trilogy – here quoted by Adeline Johns-Putra, in her 2019 book Climate Change and the Contemporary Novel, in a section about the Science in the Capitol trilogy. The chapter is an interesting academic read, even though it is a bit unfair to Robinson in its general conclusion, as he surely does not “wilful denial” “our animality” nor supports “the arrogant claim to human transcendence”.

Robinson explicitly identifies himself as a utopian science fiction writer, and, in doing so, demonstrates a scholarly awareness of its generic history. (…) He rejects static descriptions of ‘Utopia as “pie-in-the-sky”, impractical and totalitarian’, and instead insists, ‘Utopia has to be rescued as a word, to mean “working towards a more egalitarian society, a global society”.’ Fredric Jameson writes of the Mars trilogy that, even in its conclusion, the reader is aware that the ‘achievement’ of utopia on Mars ‘must constantly be renewed’, so much so that ‘utopia as a form is not the representation of radical alternatives; it is rather simply the imperative to imagine them’.

More in general, science fiction as a genre is clearly tied to imagination as well, and can be used to conceive of utopias. Here’s Robinson in a 2009 interview: “As for science fiction, who knows what it is for. To me it is simply the literary realism of our time; (…). It’s also a good tool to sharpen up one’s thinking about the future.”

I’ll get back to the utopian aspect, but I’ll first continue the imagination angle. The next quote shows the importance of imagination for landscape, and the importance of landscape for the imagination, but also, at the same time, the danger inherent in imagination. As such, Robinson’s nature writing is tied to the other themes of the book.

North, south, east, west and all the other attributes of feng shui – these are parts of the landscape of the imagination, which is a crucial part of all landscape, of course; crucial to our placement in the real world, on the Earth as we find it. But if the reality of Earth is perceived merely as material to be passed through, then it is not really there for you, and so the imagination becomes impoverished. The Earth is the imagination’s home and body. Unless you inhabit a place – not stay in one spot, but inhabit a place, as the paleolithic peoples inhabited their places, with every bush know and every rock named – then it becomes too decentered and metaphysical; you live in the imagination of an idea. True feng shui springs forth as an organic part of the landscape itself, which we perceive rather than invent, after learning the land down to each grain of sand.

Of similar importance as the Sirius debate is Robinson’s inclusion of debates on what version of certain stories of the first antarctic explorers is right. That ties imagination to stories, and so ultimately, in a kind of postmodern mise-en-abyme twist, to the novel itself: Antarctica is a story too.

Ta Shu spoke again. ‘All stories are still alive,’ he said. ‘All stories have colours in them.’ (…) ‘This present moment – this is clear.’ Although actually the light in the tent was its usual virulent blue; but they took his point. ‘The past – all stories. Nothing but stories. All coloured. So we choose our colours. We choose what colours we see.’ [It’s of note that it is implied that also present moment is not clear, a story too, and that the question of epistemics is always relevant.]

So stories are tied to imagination, and imagination can have real world effects. Robinson ties it to ideology as well. He even repeats the reference to Althusser, 76 pages after the reference first appears in the novel:

It is eerie sometimes to contemplate how much we create our own reality. The life of the mind is an imaginary relationship to a real situation; but then the real situation keeps happening, event after event, and many of those events are out of our control, but many others are the direct result of the imagination’s take on things.

Althusser is considered a postmodern thinker, and I think the book also contains deliberate plays on postmodernism – a direction of thought Robinson explicitly name-checks a few times in the novel – I don’t remember him doing it elsewhere.

For starters there’s the set-up of important parts of the book itself: Antartica is partly a book about people trying to reenact a journey they read upon in other books. The characters raise questions about the authenticity of gear, particular routes and historical huts.

Similarly, the central mystery of the book is never fully solved: who exactly are the ecoterrorists? Did the ferals know more? Is the laywer the mastermind or isn’t he? By leaving these questions open, Robinson deliberately inserts uncertainty – the hallmark of postmodernism.

At the very end, there’s an entire section where we read a fictional machine translation of fictional Chinese, and according to the fictional character listening to the translation, the future software is not very good at translating Chinese to English. So we are reading a fictionally distorted version of a fictional future transmission that never happened. Here Robinson uses the narrative to think about authenticity, pose questions about the nature of facts and the nature of our knowledge. On top of that, the content of this ultimate postmodern fragment is again familiar: the inability to truly speak of the world, stories, literature.

‘(…) Full of lands so powerful, action so strange, you must wonder if I am transmitting you from another world. But I remind you, all this happens on Earth. This too is Earth. A world beyond all telling. (…) In a vision we share a story. Lemon said stories are false solutions to real problems. What then have we done together? Look around you. Is it all a dream only? Or are all the worlds one world? Black said, dreams commence obligation to world. Seashells say poets are the unknown government of the world. And we are all poets. So now we tell the world what next to do.’

With all of the above, I hope I have convinced you Robinson tries to weave all these different strands together, and that epistemics is the core of it all. Do we need facts to do politics? What are facts? What about imagination? What about utopian politics? Do we recognize our shared cultured & ideologies are based on stories? What part has science to play in all that?

In the remainder of this review, I’ll zoom in on a few of these topics. For starters, science as a form of utopian, ethical practice.

THE UTOPIAN PRAXIS OF SCIENCE

If we agree that science isn’t so much about facts but about the social practice of establishing consensus on what is perceived as facts, it becomes clear that science is a communal affair. Robinson obviously has written about science elsewhere, like in Galileo’s Dream (2009) or Green Earth (2004-2007), but it is in the much earlier Antarctica that he highlights this communal factor, and establishes it as important for utopia.

I’m not sure to what extent the Mars trilogy (1992-1996) focuses on science, but I would not be surprised if Robinson himself sees Antarctica as some kind of conceptual starting point in his oeuvre on the matter, in which he tried to conceptually crystalize certain strands that might have been present in the Mars trilogy already.

To get to some kind of truth, one needs to juxtapose and compare stories – a scientific, communal endeavor.

Now Jim said to Ta Shu, ‘I’ve been thinking about what you said last night, about how all our stories have coloured lights on them. I know what you mean, and to a certain extent it’s true, of course. But what good historians are trying to do, I think, is to see things in a clear light – see what really happened, first, to the extent possible, and then see how the stories about the events distorted reality, and why. And when you’ve got all those alternative stories together, then you can compare them, and make judgements that aren’t just a matter of your own coloured lights. Not just a matter of temperament. They can be justified as having some kind of objectivity.’

On a sidenote, I’ll gladly link to the best text I know about the communal nature of knowledge, and why that poses a problem in a world full of social media: David Auerbach’s The Bloodsport of the Hive Mind: Common Knowledge in the Age of Many-to-Many Broadcast Networks, on his blog Waggish.

Robinson also contrasts science with other social practices: socialism, democracy, capitalism, and already calls it explicitly ‘utopian’ fairly early in the novel.

‘Sure. First it was capitalism versus socialism, and then capitalism versus democracy, and now science is the only thing left! And science itself is part of the battlefield, and can be corrupted. But in essence, in my heart as a scientist, I say to you that it is a utopian project. It tries to make a utopia within itself, in the the rules of scientific conduct and organization, and it also tries to influence the world at large in a utopian direction. No, it is true!” he cried, noting the looks on both Wade’s and X’s faces.

Halfway the novel we get another postmodern play when Robinson introduces “The Ethical, Political and Utopian Elements Embodied in the Structure of Modern Science“, a fictional English translation of a fictional book in Spanish by fictional Chileans, a book that, in the fictional world of the novel, has a real impact:

‘(…) quite a revolution in scientific circles. Because what it demonstrates very clearly is that what we think of as neutral objective science is actually utopian politics and worldview already. (…) And there is a big middle section showing how various features of normal scientific practice, the methodology and so on, are in fact ethical positions. Things like reproducibility, or Occam’s razor, or peer review – almost everything in science that makes it specifically scientific, the authors show, is utopian. (…) In reality, there are a great number of scientists who are not interested in the reasons they do what they do. This makes them bad scientists in that way, but there you are. Bad work is done in every field. (…)’

I don’t think Robinson could spell his own position out more clearly, and I feel he makes a convincing case. The fact that “Antarctica is a continent ruled by scientists” also explains why Antarctica has the setting it has for this particular novel with these particular themes.

Later in the book, when there is talk of co-ops as an economical model, this too is tied to the social praxis of science:

Everyone has at least part of the habit of co-operation; this too is part of lovingknowing; for science is above all else a community of trust. The true scientist has to be intent on co-operation in a communal enterprise, or it will not work at all.

Another theme of the book is ecoterrorism, and that gets you to the trolley problem (and science) in a heartbeat. I’ve talked about this in the comments to Angus Burke’s analysis of Green Earth, on his excellent blog Utopia in the Works. I’ll reiterate some of it here.

I heard KSR talk in Brussels in November 2023, and he devoted quite some time to the fact that he hadn’t read How To Blow Up A Pipeline (2021) by Andreas Malm before he wrote Ministry for the Future, and said that his previous anti-violence stance was changed it bit because of that. While he had depicted violence in his novels because you simply have to if you aim at realism, he never really felt comfortable about it. Malm’s ideas however make a distinction between violence on persons and violence on infrastructure. The latter might be justified, Robinson said in Brussels.

But now that I have read Antarctica, what he said in the talk puzzles me, as the ecoterrorists in Antarctica basically adhere to Malm’s ideas: targeting infrastructure, not people. So what has changed in between 1997 and 2023 for Robinson? That in 1997 he didn’t feel targeting infrastructure was justified, but, given the increasing urgency of the problem, in 2023 he does? But how then did he feel 2019, when he wrote Ministry – as it is not that he wasn’t familiar with the idea of only targeting infrastructure, given the Antarctica plot? Maybe reading Malm gave him more intellectual reasons or moral justifications?

Either way, back to science, and the trolley problem. In my review of Ada Palmer’s Perhaps the Stars I’ve argued at length that it is the basic form of politics in general. Every policy decision is, in the end, a trolley problem. It always boils down to some form of moral calculus if you want ethical justification for policy decisions. The problem in the context of climate change – but I guess it’s always the problem for any policy maker – is that the future is hard to predict, and certain justifications for both regular policy and ethically inspired violence tend to hinge on arguments that are, in the end, a matter of belief & ideology. In other words, a matter of your epistemological perspective on so-called facts.

So the trolley problem – mapping how to reach utopia – itself is a kind of iteration of the inadequacy of our scientific modelling of both climate-ecology, and society, and thoroughly epistemological in nature. Robinson also touches upon this in Antarctica, albeit less explicitly, when feral leader Mai-lis talks about what kind of analysis would need to be done to get to some kind of utopia.

Mai-lis: ‘(…) It is a matter of doing a true-cost true-benefit analysis, which is to say all costs and benefits included, including so-called exterior costs, while the unpriceable aspects of the situations are also acknowledged and included. We are trying to do this in our own subsistence here, and we often talk about the feasibility of such accounting in the world generally. Environmentally safe technologies, green technologies, applied according to a humane green analysis of the costs and benefits of our various activities – calculating needs and wants, methods and technologies – this is necessary work for people everywhere. It occupies many any evening in our camps, around the table and at the computer. And most of us believe that it can be done everywhere, if – and these are big ifs – if human populations were to decline, and if people everywhere to go feral on the land.’

Later, in an interview in spring 2009, Robinson is much more explicit about it, and he shows that ethical, utopian questions can be conceived as scientific questions too. This bridges the gap between utopian politics (the trolley problem) and science. The interview was published in Polygraph as “Science, Justice, Science Fiction: A Conversation with Kim Stanley Robinson”, by Gerry Canavan, Lisa Klarr and Ryan Viu.

Why is this ideology, the scientific method, so different, and so powerful in its real world effects? I think it has to do with some kind of “ping factor” (as in sonar): its constant efforts to test its assertions against perceived reality — or the non-human, or what have you — in order to see whether the assertions actually hold up to tests of various kinds. The move to quantification came from an effort to ask questions that were amenable to this kind of test. But the method can range beyond the quantifiable, and often does. There is a utopian underpinning to these underlying questions of value that science attempts to answer along with the more obviously physical and quantifiable questions. Who are we? What might make us happy? Does this or that method work in making us healthier? These too have become scientific questions, with distinctive answers born of science’s desire to create testable assertions and tweak them in repeated reiterations and revisions. They’re not the same answers created by capitalism to these same questions, where desires and habits are encouraged that lead to profits for a certain portion of society, but deteriorating health and happiness for most people, and for the biosphere.

So, it’s not that scientific ideology has not been formulated; it has (although as a community it tends to be inarticulate about its goals). But it’s also a work in progress, continually applied and then studied and tried again, for a few centuries now, studying not just the results but the method itself, and getting better—after being shocked and humbled by some huge reverses, moments of hubris after which the idea that science had been perfected as a method was shown to be wrong and corrections were then proposed and attempted. That process continues, but always under enormous pressure to “be more profitable,” which certainly distorts its efforts. It is a clash of paradigms and systems of power.

Robinson already pitted science to capitalism in one of the earlier quotes, and in this quote – while not from Antarctica itself – the link with that other human communal practice, economy, again becomes clear.

VS. GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG CAPITALISM: POLITICAL & ECONOMICAL STORIES

Robinson coins the term Götterdammerung capitalism in Antarctica, and bookends the novel with it: both on page 36 and on pages 359 and 363 the term is used.

In effect the money that the forest and invest the profits represented was more valuable that the forest itself, because long-term value had collapsed to net present value, and so the forest was liquidated, and more money entered the great money balloon. And so the inexorable logic of Götterdämmerung capitalism demolished the world to increase the net present values of companies in trouble. And all of them were in trouble.

&

This is Götterdämmerung capitalism, this is our moment, and just as you say colonialism never ended, this feudalism has never ended, and it has nothing whatever to do with the so-called democratic values used to palliate the masses. Indeed all the armies of the world are now employed in enforcing this system against any group that takes the idea of democracy seriously.

He explains the term in a 2020 interview for Nautilus: “I call this Götterdämmerung capitalism. When the gods are going down at the end of Wagner’s opera, Götterdämmerung, they take the world down with them”.

In one of the first political fragments of Antarctica, he links economy & politics again to stories, this time in the form of myths. In the fragment he criticizes greed & the upward redistribution of wealth – which seems to be a feature of our current form capitalism.

He saw more clearly every day that the big slogan-ideas like democracy, free markets, technological advancement, scientific objectivity, and progress in history, were all myths on the same level as the feudal divine right of kings: self-serving alibis that a minority of rich powerful people were using to control the world. Modern society, like all societies before it, ever since Sumer and Babylon, was a giant fake, a pyramid scheme in which the wealth of the world funnelled up to the rich; and their natural environment was laid waste to bulk the obscenely huge bank balances of people who lived on private islands in the Caribbean.

It also becomes clear that Antarctica as a continent not only serves as a metaphor for the possibility of governing via the praxis of science, but also as a metaphor for everything that is opposed to the Western world – Antarctica being the ultimate South, the so-called undeveloped world. And so in the final part of the book Robinson shows feudalism, colonialism and capitalism all to be different sides of the same coin, each contributing to the current dire state our biosphere.

The hypocrisy of the North, on this as on so many other issues, is endless, and beyond defence. It has beggared our language. It is the major fact in the history of the world in the last five centuries, colonialism that has never really ended, but merely changed formats.

So, the problems are identified. The question then becomes: what should we do? What real life praxis should all this analysis lead to? One of the characters has a clear opinion:

You should have know, they told him. Reform will never work. It’s just another form of collaboration. But you have to do something! he protested. Of course, they said. But you have to do something that works. And nothing works but direct action.

But direct action is hard, and

The discrepancy between his beliefs and his life was nearly too much to bear.

Whatever course of action to take, Robinson has talked & written about optimism a lot. It’s why he rather writes utopias than dystopias.

In this next fragment from Antarctica, one of the characters – Val Kenning – clearly echoes Karl Popper’s famous dictum that optimism is a moral duty: “Optimismus ist Pflicht.” On a sidenote, Popper might have been inspired by Kant, who said that even in the most difficult times there is a duty to have confidence: “Auch in schwierigsten Zeiten gibt es eine Pflicht zur Zuversicht.”

And indeed she did try to make the best of things. It seemed to her that was they way one should behave (…) Making the best of things was what courage meant, in her opinion; that was right action in the face of life. And how hard it was, given how dark her thoughts had become, and how dismal everything sometimes appeared to her; how against the grain of her temperament it had become. But she kept at it anyway, as an act of will. And all it did was get her laughed at, and most of what she said continually discounted or put down, as if being optimistic was a matter of a somewhat obtuse intelligence, or at best the luck of biochemistry, rather than a policy that had to be maintained, sometimes in the midst of the blackest moods imaginable. No; the Birdie Bowers of this world were only regarded as fools. And the world being what it was, Val supposed that there was some truth in it. Why be optimistic, how be optimistic, when there was so much wrong with so much? In a world coming apart it had to be a kind of stupidity. (…) It took an effort to be optimistic, it was a moral position.

It is striking how in such an explicitly optimistic fragment, there is so much pessimism too. It is the paradox of being alive. This might be one of the clearest, most direct vistas into Robinson’s own mind in his entire body of fiction.

THE ANTARCTIC SOCIETY AS A MODEL TO MAKE YOUR OWN REALITY, TO BETTER THE WORLD

The subtitle is clear. The four quotes I present you too.

She heard the voices of her group as the conversation of those odd Brits, those strait-laced young men, strong animals, complex simplicities, running away from Edwardian reality to create their own. Say it was an escape, say it was Peter Pan; why not? Why not? Why conform to Edwardian reality, why march into the trenches to die without a whimper? In this little room they had made their world. (…) the pure existentialism of Antarctica, where they made reality, or at least its every meaning. The pathetic fallacy of the Edwardians or the pathetic accuracy of the postmoderns; nothing much to choose between them; certainly no priority, either of heroic precedence or omniscient subsequence. Just people down here, doing things. Flinging themselves out into the spaces they breathed, to live, to really live, in this their one brief life in the world. They had been in no one’s footsteps.

&

To do this in such a harsh climate, it is necessary to use techniques and technologies from many times and places, from the Sami and Inuit and other Arctic indigenous peoples, to the best of communal social theory, to the latest appropriate technologies. We take what seems right to use, from the paleolithic to the postmodern, and most of us do not worry to much about purity. We live democratically.

Because:

He was first to the axis of rotation, to a spot of planetary power in the landscape of our imagination; a gathering of all the dragon arteries into a single tight knot.

&

Then this love for the landscape that is our collective unconscious, this knowerlover’s apprehension of the land’s divine resonance, blossoms outward and northward to encompass the rest of the planet. Love for the planet radiating from the bottom up, like revolution in the soul.

Enough with the analysis already. Wasn’t this a review to begin with?

Well – Antarctica wasn’t fully successful. Especially the parts were Robinson recounts the first antarctic expeditions were less interesting to me – and that resulted in a reading experience with an uneven pace. But the novel undoubtedly manages to convey a great sense of place, and the parts that work – especially the adventure in the second half of the book – were really good.

All and all, I think this is an important novel in the oeuvre of Robinson – but it probably shouldn’t be read first if you haven’t read anything else by him.

ps – Is it a coincidence that the name of what could be considered the main character is Valerie Kenning?

The word ‘kenning’ is related to the old Germanic word for knowledge – in Icelandic it still means ‘theory’, in Dutch the verb ‘kennen’ is ‘to know’, and the Middle English ‘kennen’ also means ‘to know’ or ‘to perceive’. So indeed, Antarctica is Robinson’s epistemological novel.

It becomes even more interesting if we consider the Proto-Germanic root *kannijanan, which is the causative of *kunnanan (‘to know how’), which gets us right into praxis as well. And add to all that the truly postmodern irony that in Old-Germanic poetry ‘kenning‘ is also the term for the rhetorical device that substitutes a name.

My other Kim Stanley Robinson reviews are here: The Wild Shore (1984) – Icehenge (1984) – The Memory Of Whiteness (1985) – The Gold Coast (1988) – A Short, Sharp Shock (1990) – Pacific Edge (1990) – The Years of Rice and Salt (2002) – Galileo’s Dream (2009) – 2312 (2012) – Shaman (2013) – Aurora (2015) – Green Earth (2015, the revised Science In The Capital trilogy (2004-2007)) – New York 2140 (2017) – The Ministry for the Future (2020) – The High Sierra: A Love Story (2022).

Consult the author index for all my other reviews, or my favorite lists.

Click here for an index of my non-fiction or art book reviews, and here for an index of my longer fiction reviews of a more scholarly & philosophical nature.

Reading your analyses of Robinson’s work always gives me the impression that he has interesting ideas and a laudable willingness to explore them that many other writers lack. But I don’t think I will ever try his books again. His thoughts on science, storytelling and capitalism are very interesting, though.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I´m sure we already talked about it, but what book(s) of his did you read? Not that I want to convince you, just curious.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aurora and 2312. Quit before the end both times.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right. The only one I would still recommend to you in that case is Shaman, but that’s a novel about prehistoric man, and maybe Ministry for the Future, precisely for the non-fiction is has, which you might find interesting too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m sorry for being such a downer every time you post something about KSR. I’ll stop doing that. I’m still tempted to read Ministry for the Future because it seems a significant SF release of the last few years.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t worry, I really don’t mind – on the contrary, I welcome different perspectives, it’s always a good reminder to not take my own taste for granted. I was really blown away by Aurora back in the days, and the fact that you DNFed it makes me look forward more to my eventual reread (in 2 years or so, after I finish the Mars trilogy), and check whether I maybe was too easily impressed 10 years ago. Could very well be.

Similarly, I’d love to read your thoughts on Ministry, even should you end up not liking that. But you get no argument from me against your reasoning: it indeed is one of the few crucial, canonical texts of contemporary SF.

LikeLike

I remember going back and forth on Aurora. I really liked some chapters, and then other chapters I found stultifyingly boring. I remembered that it ended with a space ship ping ponging around the solar system, which was awesome. And then came another chapter of people surfing or something and I couldn’t get through it, it was so dull.

LikeLike

I’ve read both Shaman and Ministry, and they were quite readable, I fully recommend both. Couldn’t really get into Mars trilogy, put it on hold after the first volume.

Robinson is very smart, but sometimes too dry for me… I will try more though, including Antarctica, just at my own pace 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for chiming in! His debut trilogy is worth investigating too, not dry at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The chances of me reading Ministry are nearing 51%

LikeLiked by 2 people

😀

LikeLike

This is a very thorough analysis, above and beyond a simple review. I love delving into the nitty-gritty of the fabrics of our reality, like you’ve done here. Well done. I’ll have a look at more of his books. If SF isn’t stretching the boundaries of reality, it doesn’t really interest me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, appreciated.

As for Robinson, my go-to recommendation for readers new to him is generally Aurora, as that is maybe his most traditional scifi book – but as you can see from Jeroen’s comment, it’s all taste always. My other favorite book of his is Ministry for the Future, that’s also formally very interesting, but some people think it is not enough of a novel/story. I disagree, again, taste.

I’m not sure if you’re familiar with Greg Egan – another, very different, author to look into if you want SF that stretches the boundaries of reality.

LikeLike

Love Greg Egan, a fellow Aussie. My fave book was always Diaspora, and there was a section in it where one of the digital entities became conscious of itself as a separate being. I always thought this was a good example of how consciousness might arise, but I’ve gone through a bit of a philosophical sea-change recently and I’m not sure this is the case. I’m going to re-read it and critique it through my new Metaphyscial goggles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was a bit in dubio about Diaspora – I absolutely loved certain parts, but some of the physics went over my head.

Care to elaborate about your philosophical sea-change? I’m interested in consciousness too, and read a fair number about brains etc over the years (see my list of non-fiction reviews), but the absolute best, most thorough book about consciousness I have ever read is the massive “The Evolution of the Sensitive Soul: Learning and the Origins of Consciousness” by Simona Ginsburg & Eva Jablonka from 2019. I highly, highly recommend it, I think it’s a must read on the matter. I’ve reviewed it extensively here: https://schicksalgemeinschaft.wordpress.com/2022/11/02/the-evolution-of-the-sensitive-soul-learning-and-the-origins-of-consciousness-simona-ginsburg-eva-jablonka-2019/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great review, Bart. Your analysis is very interesting, and on point. As a side note, have you read Moon is a Harsh Mistress? A very aggressive utopia that I feel strange kinship with, especially with the idea of defending it from Earth’s greedy capitalistic military -industrial complex.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Yes, I’ve read it, 9 years ago. Don’t remember that much about it, except that I liked it. Here’s my review, an early one, I’d just started reviewing back then. Not sure what I would think of it if I’d read it now: https://schicksalgemeinschaft.wordpress.com/2015/10/09/the-moon-is-a-harsh-mistress-robert-a-heinlein-1966/

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well that’s a difficult task, briefly. We can take the convo elsewhere if you prefer. Basically, after years as a staunch materialist, and believer in scientific realism, I converted to Idealism, swayed by Prof Donald Hoffman and Metaphysical Idealist Bernardo Kastrup. Google them and you’ll get the drift. Idealism says that the world is an edgeless impersonal mind and wat we see are attenuated images of that Mind’s mental processes. I switched mainly because Idealism has better arguments for explaining the world: less paradox, more parsimony and better explanatory power. That’s a lot to throw at you, so if you want to meet in a virtual cafe somewhere and chew some philosophical fat, I’m here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting, thanks. I consider myself a materialist too – that is, on the current macro-level. What lies beneath, or questions about the origins of our current universe, and obviously the mind-body problem, etc., well that’s another matter: I have no idea, it’s mystery, a miracle, however you want to phrase it. So I’ll gladly read up on Hoffman & Kastrup. If I have any questions, I’ll sure let you know here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hoffman makes some good and really interesting points in a ted talk about the nature of perception. Kastrup is less convincing. While he says intersting things as well, the problem might be what this ´universal consciousness’ is then – it doesn’t really explain anything at a fundamental level, it just poses another problem.

Food for thought either way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Both are compelling to me for different reasons tho they have almost similar messages. Hoffman is a scientist and is proposing a scientific theory with math and experiment to back it up. Bernardo is a philosopher but uses science to back up his position. Idealism begins with what we know for sure, that we are conscious and have experience and that stands on its own and cannot be reduced to constituent parts by reductionist science.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree that for the time being, it can’t be reduced. I´m not sure if it can´t be reduced in principle.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s often true that we can’t imagine the science of the future but consciousness seems to be a special case. How do you include subjective experience into objective investigation? How does neuronal activity translate into the taste of a strawberry, or the feeling of regret? They seem to be either side of an impassable gap.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, true, but I don´t feel like universal consciousness bridges the gap either, or better, it just creates another problem by seemingly doing away with reality: even neurons might not exist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Idealism (at least Kastrup’s and Hoffman’s) doesn’t do away with reality, it just says that what we see isn’t the whole picture. And it starts from something we know to be true: that we are conscious and experiencing. It’s not an abstract theory that needs to be proven. It just proposes that it is primary and irreducible.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Okay, thanks for clarifying. I might add Hoffman´s The Case Against Reality to my TBR.

I´m still not sure about the ontology of consciousness, and I feel there some hard gap there too, in the sense of probing it´s “true” or “real” or whatever nature.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think there is a bit of semantic juggling by the reviewer and its easy to talk yourself into a corner when you are talking about reality. No one, especially Hoffman would say that reality doesn’t exist. (That’s an absurdist position) It just doesn’t exist in the form that we perceive it. He doesn’t know what the moon is, as it is in itself. But its true nature is not a grey ball in the sky. Only our 3D perception renders it as such. And all our other senses, based in time and space, would render it as such, so we can travel there and land on it. But what the moon is without a 3D brain, he doesn’t know. But it is ‘something.’ If you watch about three or four good interviews with the Don, because some people ask him hard questions, everything will become clearer. Totally fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, will do.

LikeLiked by 1 person

From an Amazon review of Hoffman´s book: “This interesting book shows how evolutionary fitness provided that we do not see, hear, smell or feel reality, but rather interpret what we perceive to create useful icons that help us to survive. Hoffman does a good job proving this important point. Hoffman then contends that the objects that are represented by the icons we create do not exist in reality. Though interesting, the argument and proof are confusing to the point they resemble hand waving. Finally, Hoffman speculates that whatever underlying reality is has consciousness. It is hard to understand how this speculation follows from the more well-supported portions of the book.”

I had a bit the same feeling after watching the talk. So what you are saving is that the reviewer is wrong, and that Hoffman doesn´t claim reality does not exist, just that it is different from our perception. Okay, but how can he claim it exists, if our perception might be wrong or at least incomplete?

LikeLike

I think another review, by EBTX, captures my objections well.

LikeLike

I’ve skimmed through most of the second half of this because I’ve read enough to think this may be the KSR novel for me to gain an entrée to his work. It sounds fascinating and right up my street in how I think speculative novels best work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Best read a broad synopsis or so elsewhere, as I hardly talked about what the book is about on a plot level, and if it still appeals to you, by all means, I’d love to read your thoughts on this book. Could you say something in general about how you think speculative novels best work?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like speculative fiction – fantasy to SF and all in between – much as I like most fiction, to be informative, entertaining and enlightening: to tell me something about human nature, to challenge me, and also to let me find something to admire in the way the author has tackled the work, in plotting, language, ideas. Is that too much to ask?! 😁

LikeLiked by 1 person

Measured against all the muck that is being published, it is too much to ask!

LikeLiked by 1 person

If someone’s never read KSR, where should they start?

LikeLike

That’s not that easy to answer, because his books are pretty different – even though they generally share more or less the same themes.

‘Aurora’ was my first, and that hooked me. It’s about an interstellar ship on a way to colonize another starsystem. KSR tries to show why that is biologically impossible. Also has some social stuff on the crew, and a fun part with an AI as narrator that learns to tell a story throughout the novel.

‘Shaman’ is about prehistoric people, not scifi at all, but very human. It’s the least ‘speculative’ so to say, and as such maybe his most ‘normal’ book.

‘New York 2140’ is about how NY, in 2140, is permanently flooded due to sea rise, and has lots of different things going on.

‘Ministry of the Future’ might be his most ambitious work, trying to write a realistic story about how the worst of climate change might still be mitigated the next 70 years or so. It’s formally challenging for some, as it has significant doses of non-fiction, and that results in some people missing the very human story the novel presents as well. I thought it was brilliant, very free in its authorial voice and its approach what a book should be.

‘Green Earth’ is about 1000 pages, and focuses on scientists & politics in Washington DC, a very rich book, climate change obviously also a theme, and maybe the one that’s most focused on characters in his oeuvre.

I hope other KSR fans read this comment too, and chime in. What would be your recommendation for a first KSR?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aurora sounds pretty interesting; I have a copy of Red Mars somewhere, too, I believe — how does that stack up?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I haven’t read Red Mars, I kept the Mars trilogy for last. It´s considered his magnum opus, it won awards, but from what I gather some people find it dry. Either way, it´s the definite book about Martian terraforming, and by many considered as the best example of Hard SF.

LikeLike

Unless you are a sucker for Mars, I´d try Aurora first.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Consider Aurora on the list 🙂 Many thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

The first two Mars books put me off KSR, but your reviews always give me a push to wanna try again. They thoughts on epistemology are interesting enough here to maybe give this a shot.

At some point.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You did read the second book? What put you off?

LikeLike

Hey Bart, the other Bart is back! Hope you are well. Remember when I commented on one of your KSR reviews asking for recommendations, since I loved Years of Rice and Salt and High Sierra? Well, my reading pace has slowed so drastically this year with schoolwork that I’ve probably read four or five books total since then, none by KSR. I’m trying to decide between Red Mars, which I recently snagged a copy of, Aurora, based on your recommendation, Ministry, because as a young person, the climate is incredibly important to me, and this, because I’ve always just had a thing for Antarctica (and the Arctic – my favorite piece of travel writing ever, hands down, is Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez, and I am obsessed with the winter travel in The Left Hand of Darkness). I don’t want you to decide for me, obviously, but I’d be curious for you to weigh in again. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Though advice. My own way to select what book to read next always is ´mood´ – what do I feel like reading at this moment. Somehow I´m always more draw to something than something else.

But given what you´ve written, I´d go for Ministry – in a way his crowning achievement, both formally and contentwise. And since you loved High Sierra, the non-fiction parts should appeal to you.

LikeLike

On the other side of the coin from you, I have read KSR’s Mars’ trilogy but not this one. You write above that Antarctica may be a conceptual starting point for Mars. I read somewhere else that Antartica is like a concentrated version of the Mars trilogy. When we get to the other side we’ll have to compare notes. 🙂

And when you do finally make the decision to read Green and Blue Mars, enjoy. Red Mars is the weakest of the three… There is a companion collection of short stories (The Martians) in which Robinson threw the cutting room floor material for the novels, but only a few are worth the while. The story featuring a climb of Olympus Mons is great, however (“A Martian Romance”).

Regardless, great review. Love the in depth analysis.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can see this might be a concentrated version of the Mars trilogy: inhospitable environment, details about traveling through it, some strife between political factions, questions about how to organize, etc. I will keep the question in mind when I start Red Mars – hopefully before the end of the year.

When I eventually finish the trilogy, the short fiction is all that’s left: The Martians, Escape from Kathmandu and a collection of short stories. I’m fairly positive I’ll enjoy most of it.

Thanks for the compliment, it’s been some time since a book prompted a long analytic review like this – I think my latest was on Ada Palmer’s final Terra Ignota book, almost 2 years ago.

LikeLike

Pingback: WHAT CAN WE HOPE FOR? – Richard Rorty (2022) | Weighing a pig doesn't fatten it.