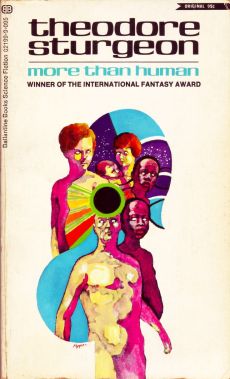

Theodore Sturgeon is one of SF’s greatest short fiction writers, and so it is apt that More Than Human stems from a novella, Baby Is Three. Sturgeon added a part before and a part after. Each part is quite distinct, 3 novellas if you will, but taken as a whole, they are yet another, different thing. Readers familiar with this book’s content will not find that surprising: More Than Human is roughly speaking about a mind-reading idiot, teleporting twin girls, a retarded baby with a supermind and a telekinetic girl, together forming something new: the “Homo Gestalt” – something more than human indeed.

Theodore Sturgeon is one of SF’s greatest short fiction writers, and so it is apt that More Than Human stems from a novella, Baby Is Three. Sturgeon added a part before and a part after. Each part is quite distinct, 3 novellas if you will, but taken as a whole, they are yet another, different thing. Readers familiar with this book’s content will not find that surprising: More Than Human is roughly speaking about a mind-reading idiot, teleporting twin girls, a retarded baby with a supermind and a telekinetic girl, together forming something new: the “Homo Gestalt” – something more than human indeed.

I’ll make a few general remarks on content and writing first, and elaborate a bit about the philosophical foundations of this book in the second part of my review – Friedrich Nietzsche, oh yes!

Obviously, the fifties were a different time, and parapsychology and the likes still held great promise. I started my reviews of Childhood’s End and The Demolished Man in the same fashion. So yes, this is science fiction, even though it might read as psychic fantasy at times. Sturgeon even gives a kind of hard SF explanation for his premisses, should his reader have trouble with suspension of disbelief.

“It would lead to the addition of one more item to the Unified Field – what we now call psychic energy, or ‘psionics.'” “Matter, energy, space, time and psyche,” he breathed, awed. “Yup,” Janie said casually, “all the same thing (…).”

But I have no interesting in pointing out where More Than Human feels a bit dated, as it remains an outstanding novel. Approach this simply as you would approach a contemporary novel like Susanna Clarke’s: a supernatural tale.

The first part of the book focuses on the early life of the idiot, living in the woods, being one with nature. Certain parts felt like something Ralph Waldo Emerson or Henry Thoreau could have written. Imagine my delight when I read on Sturgeon’s Wikipedia page he was a distant relative of Emerson. Sturgeon’s prose is a treat. At times it has a bit of formal ring to it, but there’s great lines throughout.

It was spring, the part of spring where the bursting is done, the held-in pressures of desiccated sap-veins and gum-sealed buds are gone, and all the world’s in a rush to be beautiful.

or

It was a treasure-proud silence, and Lone felt it change as a man’s kind of pride might change when he turned from a jewel he treasured to a green shoot he treasured.

Sturgeon’s economical style manages to paint emotions and whole backstories in only a few, precise lines. He could’ve just as easily turned to poetry, if he’d liked to do so.

Little Hip Barrows was a brilliant and beautiful child, to whom the world refused to be a straight, hard path of disinfected tile. Everything came easily to him, except control of his curiosity – and “everything” included the cold injections of rectitude administered by his father the doctor, who was a successful man, a moral man, an man who had made a career of being sure and being right.

or

She did not say goodbye, though she felt nothing else.

1953 was close to the Second World War, and for contemporary readers it’s hard to imagine what that must have felt like. I’d like to quote just one more example of Sturgeon’s mastery, in which he describes the wife of soldier – who recently got a telegram her husband won’t be coming back – doing simple, everyday things, but with great significance.

Wima knew before she started that there wasn’t any use looking, but something made her run to the hall closet and look in the top shelf. There wasn’t anything up there but Christmas tree ornaments and they hadn’t been touched in three years.

A big part of the book’s strength isn’t the speculative bits, but the real emotions of ordinary people.

In part two and three the narrative voices change, part 2 – Baby Is Three – has a first person narrator, and introduces a bit of mystery into the story. The last part is called Morality – yet something else with an Emerson ring to it – and zooms in on a new character. I have to say I liked the prose and general vibe of the first part best, but that doesn’t mean I didn’t enjoy reading the rest of the novel: I did.

NIETZSCHEAN PERSPECTIVES IN SF: ETHICS, LONELINESS & HUMILITY

I liked it so much because More Than Human resonated with how I experience life and existence. There’s a few instances on the non-existence of the freedom of the will, and in one Sturgeon manages to couple that with a Nietzschean view on morals.

But the cornerstone of the work we’re doing is this: there’s a chain of solid, unassailable logic in the things we do. Dig deep enough and you find cause and effect as clearly in this field as you do in any other. I said logic, mind; didn’t say ‘correctness’ or ‘rightness’ or ‘justice’ or anything of the sort.

There’s a strong sense of Beyond Good & Evil in More Than Human. Nietzsche must have been an important inspiration for this book, as the concept of the “Übermensch” – a future human with his own set of moral rules – clearly resembles certain elements of the Homo Gestalt. Janie, one of the superhuman’s components, even compares the Homo Sapiens to goats that surround the Homo Gestalt. Nietzsche used similar metaphors to explain the concept of the Übermensch. That concept has tragically been abused by Hitler and his ilk, and still is often misunderstood. Sturgeon’s aim with More Than Human really is similar to Nietzsche’s: freeing humanity of enslaving morals (“habits”), on a path to self-respect and ethics (“an individual’s code”). Obviously this was something that was needed even more back in the morally restrictive 1950s than it is nowadays, but it remains an ongoing, incomplete process.

On top of that, and maybe even more importantly, there is this deep sense of material awareness, an awareness that we are the result of a process, an awareness that we are grounded, rooted, that we are earth – something a very different novel like Aurora pointed out too. (Also of note in the following quote is the occurrence of the word “laughing” – one of Nietzsche’s major works is The Joyful Wisdom, and a positive, affirmative gaiety is an important feature of the Übermensch.)

And here, too, was the guide, the beacon, for such times as humanity might be in danger; here was the Guardian of Whom all humans knew – not an exterior force nor an awesome Watcher in the sky, but a laughing thing with a human heart and a reverence for its human origins, smelling of sweat and new-turned earth rather than suffused with the pale order of sanctity.

And so ethics becomes ‘being self-aware’, and learning some humility at the same time.

What it is really is a reverence for your sources and your posterity.

As such, ethics becomes a shield against loneliness, an important theme in the first part of the book, and, again, very much a Nietzschean feeling too. Knowing you are but a node in a long line of nodes helps when feeling alone.

“Everybody’s alone.” He nodded. “But some people learn how to live with it.” “How?” (…) “Because of something you don’t know anything about. (…) It’s sometimes called morality.”

Nietzsche is considered elitist by some, as is the now famous Sturgeon’s law. There’s an echo of that in More Than Human too, but this time with an ethical dimension to it, when considering the intentions of his fellow humans.

“I’d say from what I know of people that only two kinds are really progressive – really dig down and learn and then use what they learn. A few are genuinely interested; they are just built that way. But the great majority want to prove something. They want to be better, richer. They want to be famous or powerful or respected. (…)”

Such views might lead to loneliness indeed. Ethics is a supportive shield, yes, but love too. The fact that love is something material in our brains doesn’t diminish it. You can be a materialist and a romantic at the same time, as these great, great quotes prove.

“When we poor males start pawing the ground and horning the low branches off trees, it might be spring and it might be concreted idealism and it might be love. But it’s always triggered by hydrostatic pressures in a little tiny series of reservoirs smaller than my little fingernail.”

and

(…) love’s a different sort of thing, hot enough to make you flow into something, interflow, cool and anneal and be weld stronger than what you started with.

So it seems that just as Nietzsche was a sentimental sucker – cracking when he saw an old horse being beaten – also Sturgeon is yet another example of one of the great human paradoxes: having feelings and being sharply analytical, or, in the terms of that other false dichotomy: heart + head.

Contrary to The Demolished Man or Childhood’s End, More Than Human is no 1950ies pulp. Sturgeon is a literary writer, and More Than Human deserves a greater audience than just speculative fandom.

Great review.

I love this novel – for me, it is one of the most quotable of all SF novels. As you say, Sturgeon was a genuinely good literary.writer.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks! Yes indeed, I had several more quotes lined up, but had to restrain myself 🙂

LikeLike

I’m pretty sure I did read this novel back in my days of discovering SF, but I can’t remember it (sadly, a few decades can do that your memory…) and now I want/need to explore it once again. Thank you! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad to be of service! 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have to confess, I have quite honestly never heard of this author or any of his works! I feel like I have some catching up to do 😮

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s the only thing I read if his too. I’ve ordered another of his novels, Cosmic Rape, a few days ago, and plan to get a short story collection, but I have yet to decide which…

LikeLike

Great review. Sturgeon is one of those ’50s SF writers who I think holds up really well today, thanks to the literary aspects of his work… books like this one and The Cosmic Rape hit on some fascinating themes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! From what I’ve read of 50s SF so far (only a few titles I have to admit) it’s just this and the Foundation trilogy that really hold up. But there’s so much I have yet to read… Cosmic Rape will be my next Sturgeon, I wonder how they’ll compare.

LikeLike

Pingback: WHIPPING STAR – Frank Herbert (1970) | Weighing a pig doesn't fatten it.